Chittenango Ovate Amber Snail - The Story of an Uncommon Mollusk

A Chittenango Ovate Amber Snail (COAS) explores a new leaf that was placed inside its terrarium. They have a specialized diet that snail researcher Cody Gilbertson has fine tuned during her years caring for them.

Specialized Habitat: Chittenango Falls State Park, New York

Visitors to Chittenango Falls State Park just outside Cazenovia, New York may notice a curious sign at the base of the falls during their visit: “Endangered Species Habitat, Keep Out.” This intriguing notice marks the fenced-off area protecting a New York State Department of Environmental Education (NYSDEC) listed endangered species that is so rare and specialized that it can be found nowhere else in the world apart from the small habitat surrounding the falls. These small Chittenango Ovate Amber Snails (COAS), many with tiny numbers affixed to their shells, move slowly about their protected microhabitat undetected by humans.

After a 2019 survey, snail researcher and expert Cody Gilbertson, M.S. estimates that there are only 50 Chittenango Ovate Amber Snails (COAS) left in the wild and she is concerned that they will find even fewer individuals during the next survey. The snails are counted each year by a team lead by US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) who manages the snails and recovery program in collaboration with Rebecca Rundell’s, Ph.D., lab at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF). What makes this snail so rare and what’s being done to protect their future?

The only known habitat for the critically endangered snail is in the fenced off area surrounding Chittenango Falls in Chittenango Falls State Park in New York state.

Threats Facing the Endemic Snail

The snails were first described in 1908 by mollusk biologist Henry Augustus Pilsbry as a subspecies of another snail, Succinea ovalis, but later it was determined that the snails were genetically distinct from the oval amber snail and reclassified as Novisuccinea chittenangoensis, a species new to science. Their distinct evolutionary history is likely in response to the unique geological features of the waterfalls that separated them from other snails in the region. While fossil records indicate the snails may have previously had a larger range, there has never been a colony of COAS snails discovered outside of Chittenango Falls.

It is unknown why COAS numbers are decreasing now, however, rock slides, other snail species out-competing COAS for resources, invasive plant species such the pale swallow-wort that choked out many native plant species, climate change, as well as humans trampling of the snails and their habitat may be contributing factors. In 2006 half the wild population was also lost due to a massive rockslide at the waterfalls, which crushed many of the snails and a large portion of their home. Survival can be difficult when you are a little invertebrate who only lives in one small, specialized habitat.

Captive Breeding Program

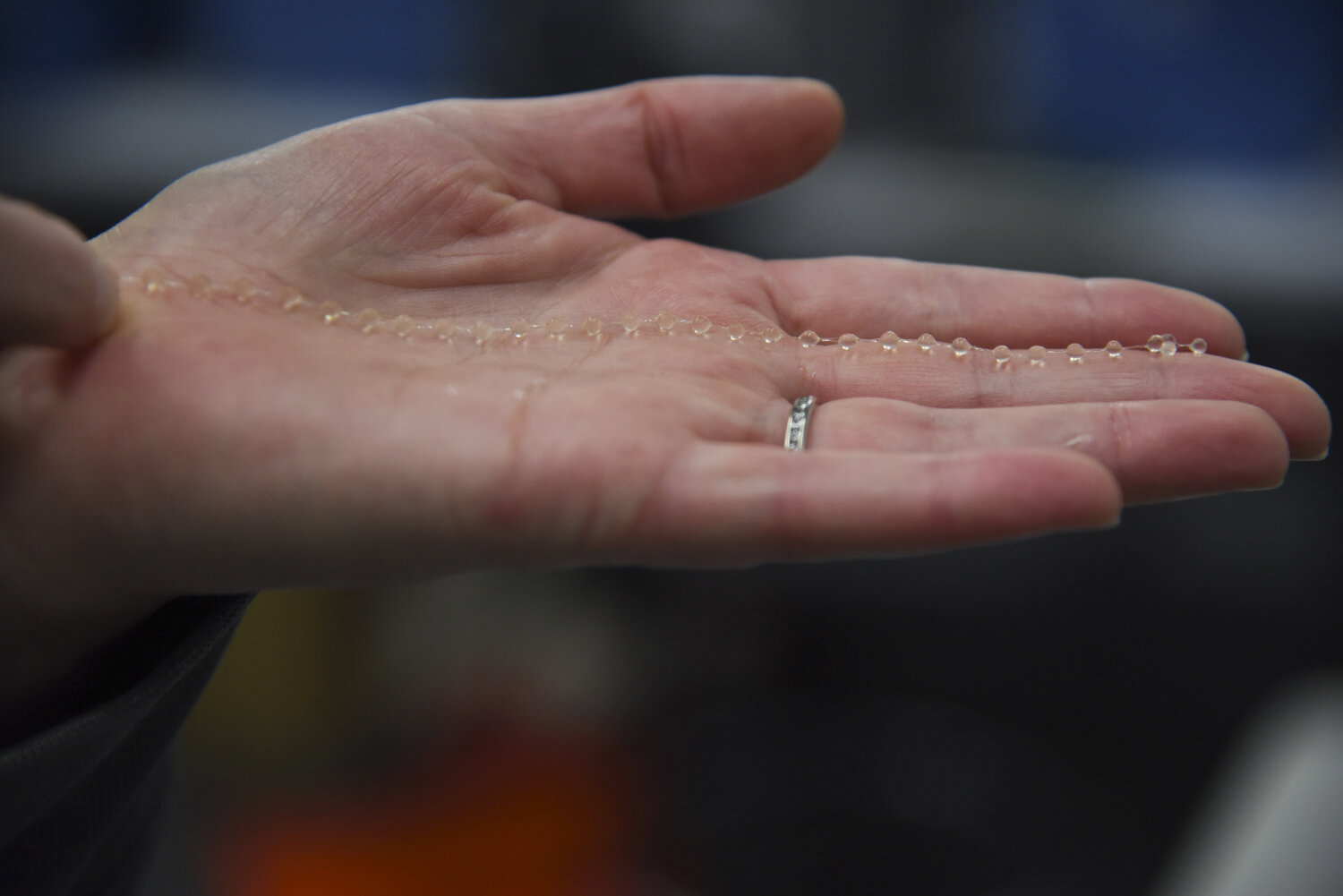

In order to increase their numbers, the COAS research team brought ten snails into the lab to study them and start a captive breeding program. But figuring out what the snails ate, proved to be difficult. A synthetic diet often fed to other snails wasn’t working. It wasn’t until Gilbertson discovered a tiny stowaway snail that was attached to vegetation collected near the waterfalls that she made a breakthrough. She received permission to keep this snail and observed what it ate. She would then would go out in the field and collect more of its preferred leaves and was thereby able to expand upon this new-found knowledge of the COAS diet.

Gilbertson and other members of the COAS program have since developed a successful captive breeding program, which currently houses between 400 - 500 snails. These snails are slowly released into the wild each year to join the existing population.

Snail Diet and Husbandry

Gilbertson developed COAS husbandry practices during her master’s research at SUNY-ESF and now she and research support specialist Ashton Yost, who she has trained, are the only two people in the world who know how to care for the snails. They painstakingly harvest native leaves throughout the year, collecting sun-bleached sugar maple in spring or native paw paw or black cherry that grow near the campus at just the right stage of decomposition for snail consumption. Student volunteers from SUNY-ESF help contend with the large piles of leaves that they collect, sorting them by species and level of decomposition.

Then each week Gilbertson and Yost sit in a temperature-controlled room at 15C (59F) in the winter and 20C (68F) in the summer (to mimic outdoor temperatures) while they carefully clean each snail community’s terrarium, making sure each snail is accounted for before replacing the leaves with a complicated “snail sandwich” recipe. This recipe of different species of native leaves at different levels of decomposition is changed out each week based on what each small community has decided to eat.

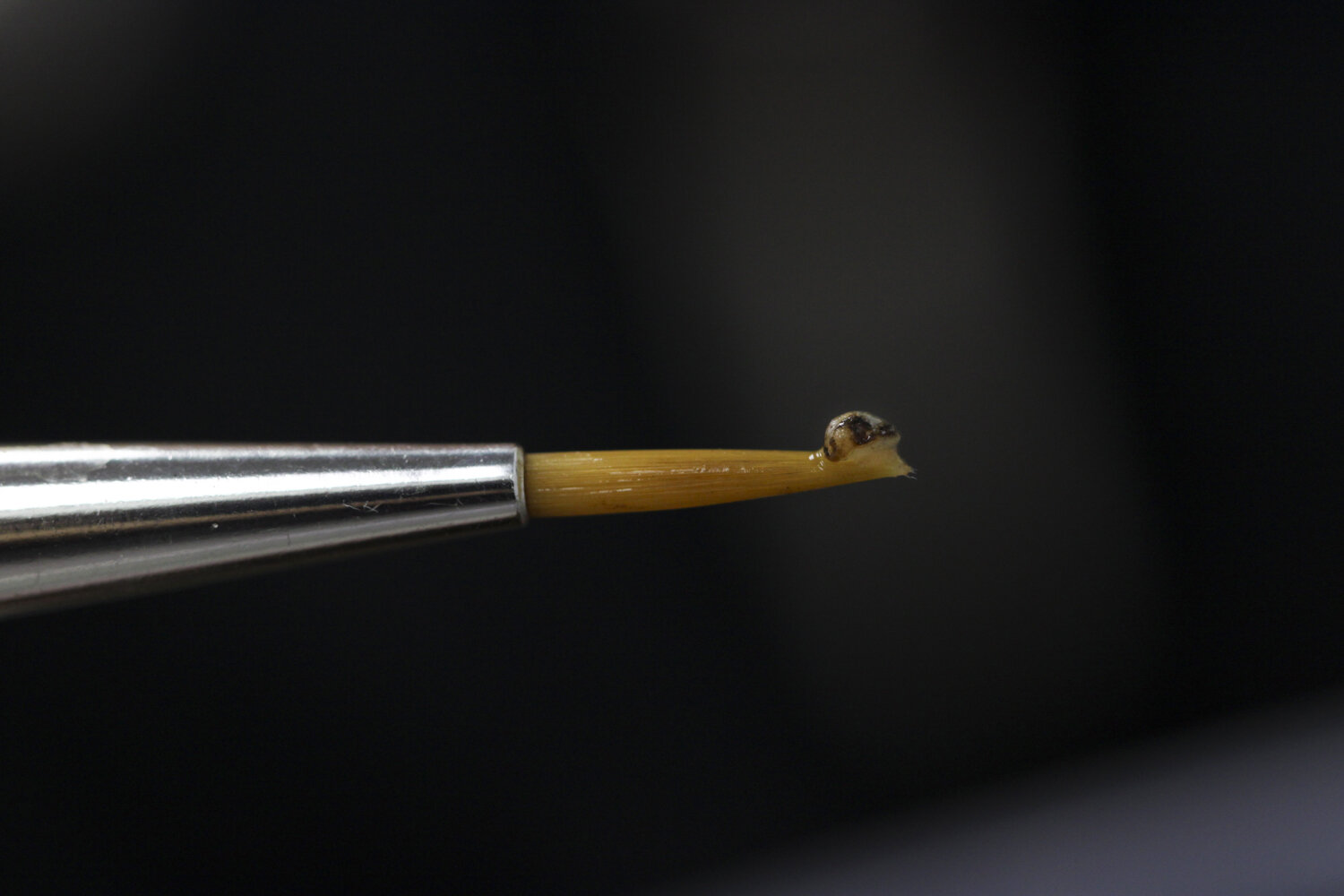

Snails use their radula, a structure of tiny teeth rows, to scrape food such as leaf fiber into their mouths. Their handiwork can often be spotted in the forest; leaves that have been stripped of their fiber and left just a skeleton of leaf veins and stems. Gilbertson and Yost make selections from various boxes containing leaves separated by species. The leaves are then sprayed with water collected from Chittenango Falls to ensure the best replication of the habitat before being placed back in the terrariums.

Rosamond Gifford Zoo Snail Colony

The Rosamond Gifford Zoo in Syracuse, New York also houses a secondary colony of about 150 COAS where Gilbertson and Yost also take care of the snails. The snails are cared for underground in what the zoo calls its “hibernacula,” or place where an animal hibernates for the winter (during the winter months COAS survive the extreme temperatures, ice, and snow that they experience at Chittenango Falls, by sealing up their shells in hibernation). The snails are not on public display at the zoo yet, but they hope they will be soon. However, a statue of a COAS that was designed by local artist Kate Woodle sits in the children’s play area at the zoo, promoting the native species in a public space.

Snailblazer’s Facebook Group

Another way that COAS are celebrated and promoted is through the Facebook group “Snailblazers.” Gilbertson and other members of the online community use the platform to share snail news, promote education and understanding of the species. They also photograph the snails in tiny festive dioramas. These photos are met with much online enthusiasm. Yost recently created a birthday party scene for Hatch Jr., the oldest COAS snail on record at 4.5 years old (the average lifespan of wild COAS is only 2.5). Small party hats were perched on top of the snails’ shells. They also threw a holiday party last year for the snails complete with a winter scene, presents, and a Santa snail.

The Future of the Critically Endangered Snail

What does the future of this small, charismatic snail look like? Could some plans for new signage at Chittenango Falls help prevent people from trampling the snails and their habitat? Could some positive PR and cute photos of snails help garner more support and understanding for the snails?

Snail advocates suggest some ways visitors can help the snails. They ask when visiting Chittenango Falls to stay on the designated trails, not to enter the fenced-off area that protects their habitat, to keep pets on their leashes, pack all your trash out with you, and to ask about volunteering or consider donating to snail conservation through the Rosamond Gifford Zoo (make sure to write COAS project in the notes)! To learn more about their snails visit www.dec.ny.gov/animals/7122.html.

Chittenango snails have four tentacles. Two longer ones on the top of their head where their eyes are attached and two below that they use to sense and feel around their environments.